This report contains graphic and sensitive content

Before the first gunshot was fired in Bawku and renewed violence erupted in November 2021, the conflict had gathered enough steam on social media – WhatsApp, Facebook and TikTok. For over four decades, the sporadic ethnic conflict between the Kusasis and Mamprusis over rights to the Bawku chieftaincy skin (throne) has persisted. However, never has the area witnessed such sustained violence for more than two (2) years. According to Simon Asimiga, a journalist with Source FM who was interviewed for this report:

“Social media has played a significant role because years ago, when there was (a) conflict in Bawku, it would last for at most a week. But now when someone is killed, it is put on social media, and when his people see it, they will sponsor and demand revenge.”

According to the Bawku Municipal Assembly, more than 200 victims have so far lost their lives due to the conflict. However, other sources suggest this figure could be much higher. A journalist with Gumah FM in Bawku, Nurudeen Gumah in a radio broadcast claimed: “There are records that indicate that from 2021 till date[2023], more than 800 people have died in the Bawku conflict.” This assertion is occasioned primarily by the fact that many deaths are hidden from officials and thus are unaccounted for:

“Many people [have] died, and their bodies were never given to the Police. Police are not aware of them and so, because of that, it will be difficult to ascertain the exact number of persons who have been injured or who died,” the lead government representative in the Bawku municipality, Amadu Hamza, conceded.

Insights from the community suggest the feuding factions may be deliberately choosing not to disclose casualty counts on their sides as a strategy to launch more punitive retaliatory attacks on their opponents. At the least, it is a show of superiority over the other; as disclosing casualties on your side can be perceived as losing.

Also, the Police/Military find it difficult to access some of the remote areas where the fighting is intense, while the resort to traditional/religious burial demands (where a body is buried on the same day of death) makes it difficult to properly account for casualties of the conflict. These are some of the reasons contributing to the lack of reliable data regarding the conflict deaths and injuries so far.

On one of the bloodiest days in the ongoing ethnic conflict – September 21, 2023, unknown gunmen killed nine (9) people and injured 17 others in Pusiga. A Bawku situation tracking report by the West African Network for Peace Building also showed how 23 people were killed in 11 days in the area due to the conflict. Reports have emerged about the killing of a pregnant woman and a 2-year-old child because they belonged to either of the two conflicting groups, Kusasi or Mamprusi or were perceived to have sympathies for either side.

Sometime in 2023, the government deployed about 1000 soldiers from the Ghana Armed Forces to the area to help stabilise the security situation and has since November 2021 imposed a curfew on the Bawku Municipality and its environs; reviewing the curfew hours at different points.

Doxxing on Facebook

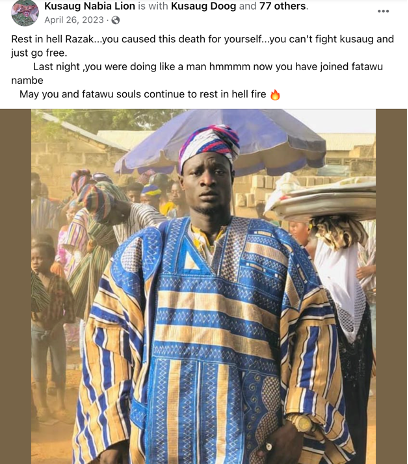

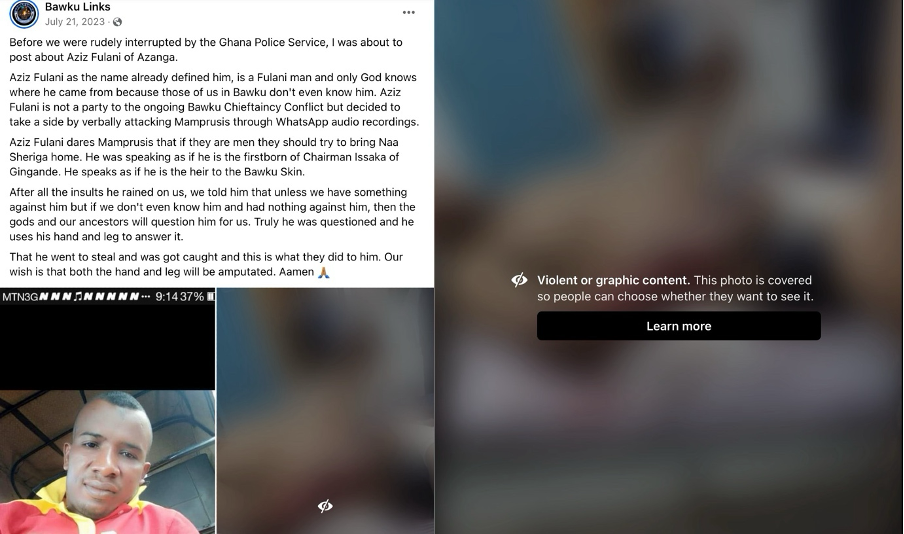

Doxxing – is the malicious search for and publishing of private or identifying information about an individual on the internet with the intention to cause harm. In researching this report, GhanaFact investigations found that for some people killed in Bawku, targets were first put on their backs on Facebook by the splashing of their pictures amid threats on the popular social media platform. Subsequently, these persons were killed.

A simple Facebook search using the keyword “Bawku” throws up several pages and individual accounts actively involved in doxxing, spreading hate speech, using dog whistles to incite violence and displaying pictures of dead victims as human trophies, which are some of the tactics that the online actors have employed from the two feuding sides.

Fig 1: Threatened on Facebook on February 17, 2022 (here) and killed in February 2023 (here)

Fig 1: Threatened on Facebook on February 17, 2022 (here) and killed in February 2023 (here)

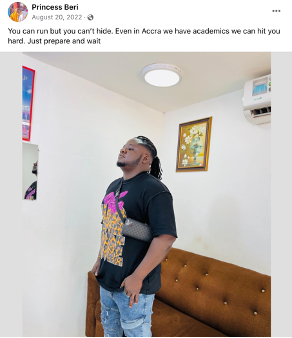

Fig2: Threatened on August 20, 2022 (here)

Fig2: Threatened on August 20, 2022 (here)

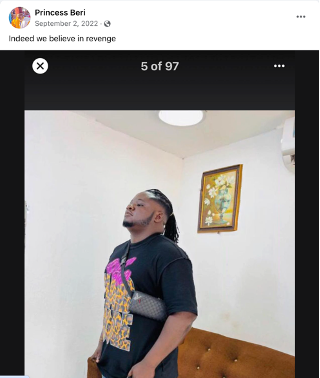

Fig 2i: Celebratory post after his death made on September 2, 2022 (here)

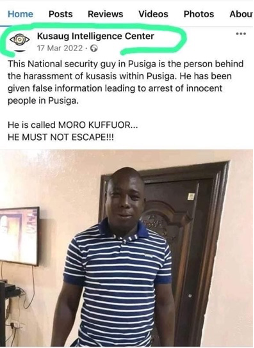

Fig 3: Threatened on March 17, 2022 (Now deleted Post) and subsequently killed

Fig 3: Threatened on March 17, 2022 (Now deleted Post) and subsequently killed

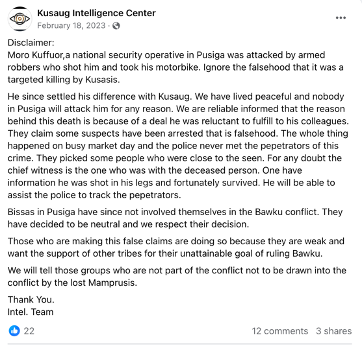

Fig 3i: Disclaimer (here) posted on February 18, 2023, after the killing of Moro Braimah

Fig 3i: Disclaimer (here) posted on February 18, 2023, after the killing of Moro Braimah

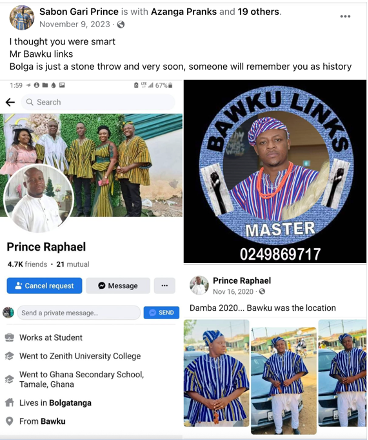

Some of the prominent pages, groups and individual accounts that are neck deep in the online battle for supremacy for Bawku – agenda-setting and shaping narratives – include Bawku links, Kusaug Intelligence Center, Bawku Traditional Area, Kusasi Voice Association, Voice of Mamprugu, T Blow Nash(Mamprusi), Rashid Kabore(Kusasi), Bawku Kurkur Kusasis(Mamprusi), Sabon Gari Prince(Kusasi), Kusaug Nabia Lion and a host of others.

Meanwhile, several other persons are continuously threatened on Facebook and may just be awaiting their fate if nothing is done to avert it.

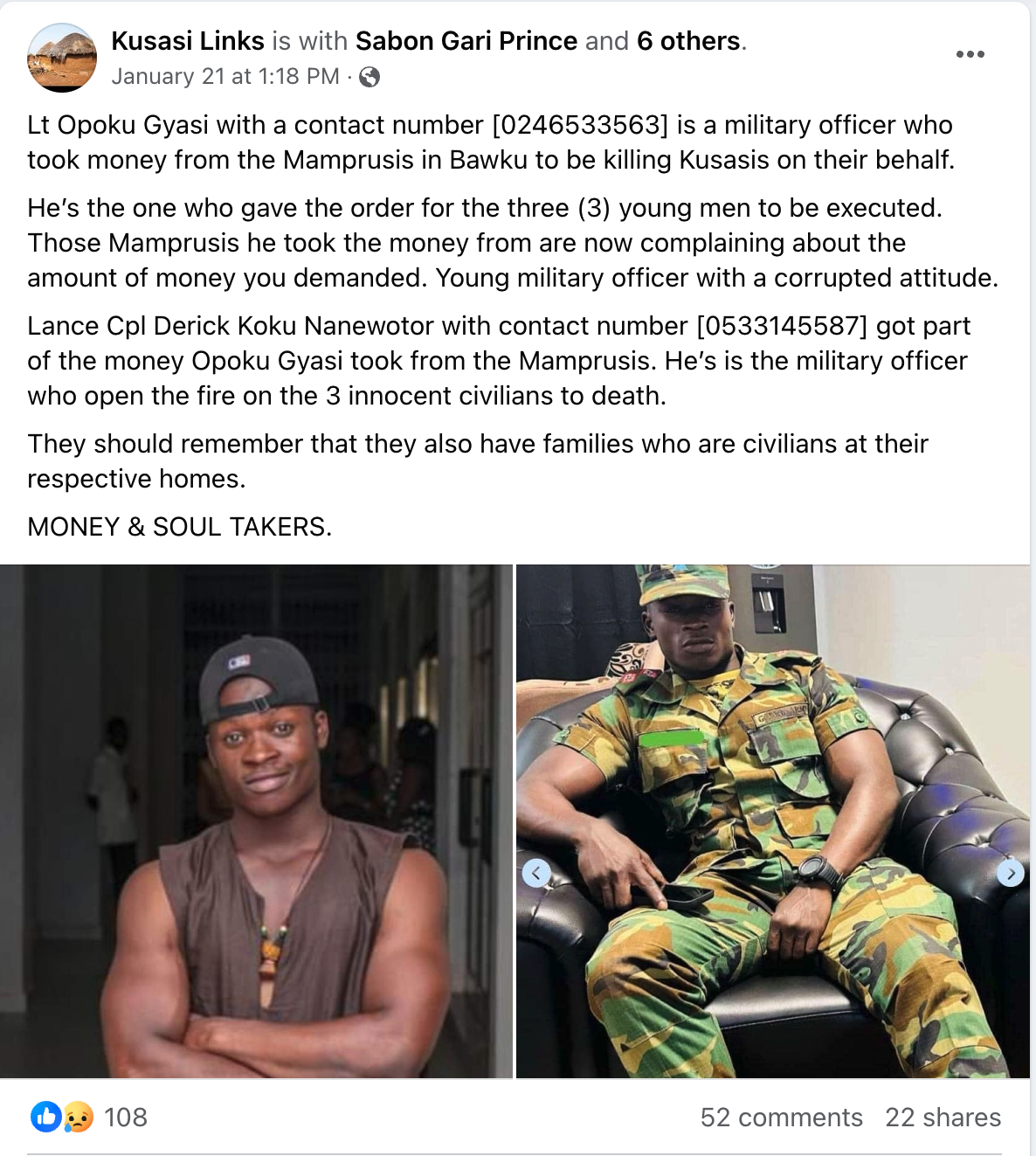

Fig 4: A threat against a serving military officer on Facebook

Fig 4: A threat against a serving military officer on Facebook

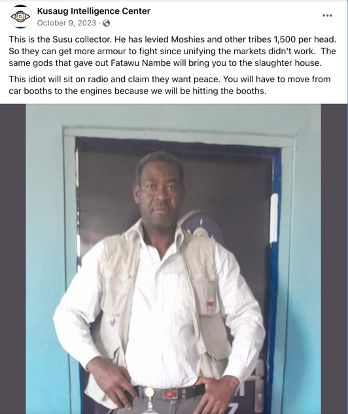

Fig 5: One of several others threatened on Facebook

Fig 5: One of several others threatened on Facebook

Fig 6: One of several others threatened on Facebook

Fig 6: One of several others threatened on Facebook

Fig 7: One of several others threatened on Facebook.

Fig 7: One of several others threatened on Facebook.

Fig 8: One of several others threatened on Facebook.

Fig 8: One of several others threatened on Facebook.

Threats against journalists on Facebook

Traditional media, particularly radio, has played a major role in the ongoing Bawku conflict – for both the good and bad. The offensive use of radio programs by journalists in the conflict locality is increasingly a major driver of the mutating nature of the conflict. In particular, these radio personalities are becoming beholden to their adverse or contravening acts, which further polarizes their audiences to sustain and intensify the conflict.

Ghana’s media regulatory agency in October 2022 expressed concerns over the increasing weaponization of the media and in a statement said it had: “noted an escalation in incidences of hate speech, disinformation and incitement on (the) radio of a scale and scope that pose a clear and present danger to the Bawku community.” The National Media Commission (NMC) said its monitoring showed that what was happening in Bawku was closely reminiscent of the egregious misbehaviour of Radio Television Libre des Mille Collines (RTLM) in the Rwandan genocide.

Even though the NMC fell short of naming radio stations, any close watcher of the Bawku conflict or simply monitoring the Facebook pages of Gumah FM, Bawku FM and Source FM show, the three media houses are very much aligned with the conflicting parties and sometimes serve as the mouthpiece of key actors in the conflict. While researching for this study, GhanaFact’s social media monitoring has exposed threats on Facebook against five (5) journalists in Bawku.

“Apart from going to work, I’m always home. My name and pictures are always being put on social media by these pseudo accounts and I’ve reported these threats to the police and military,” a journalist with Gumah FM in Bawku, Nurudeen Gumah said.

Fig 9: Nurudeen Gumah of Gumah FM threatened on Facebook

Fig 9: Nurudeen Gumah of Gumah FM threatened on Facebook

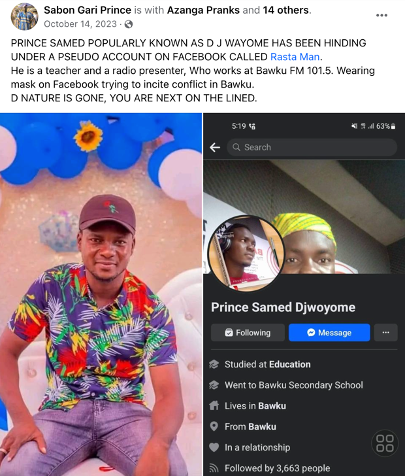

Fig 10: Prince Samed of Bawku FM threatened on Facebook

Fig 10: Prince Samed of Bawku FM threatened on Facebook

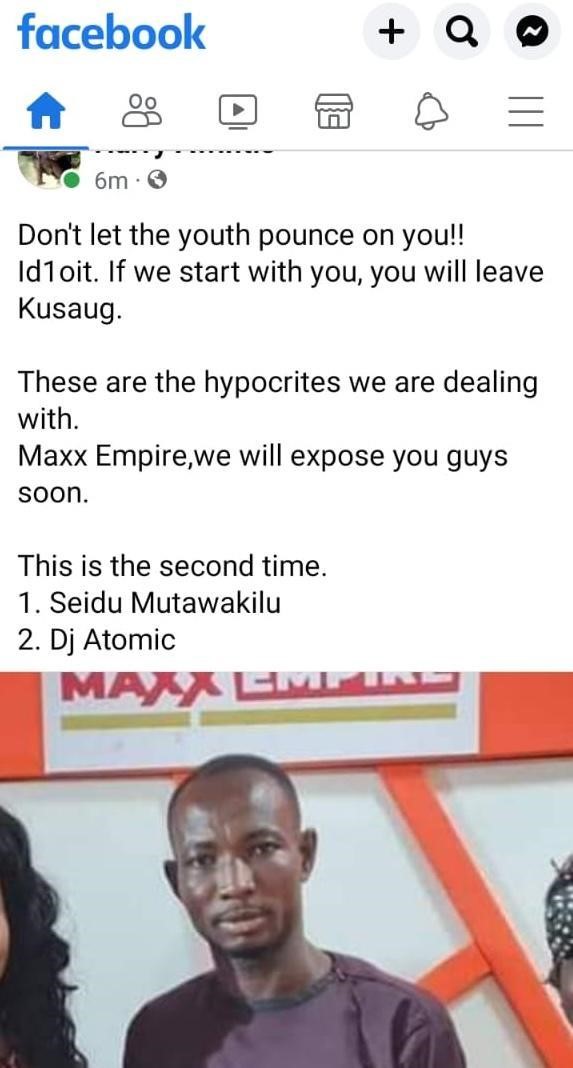

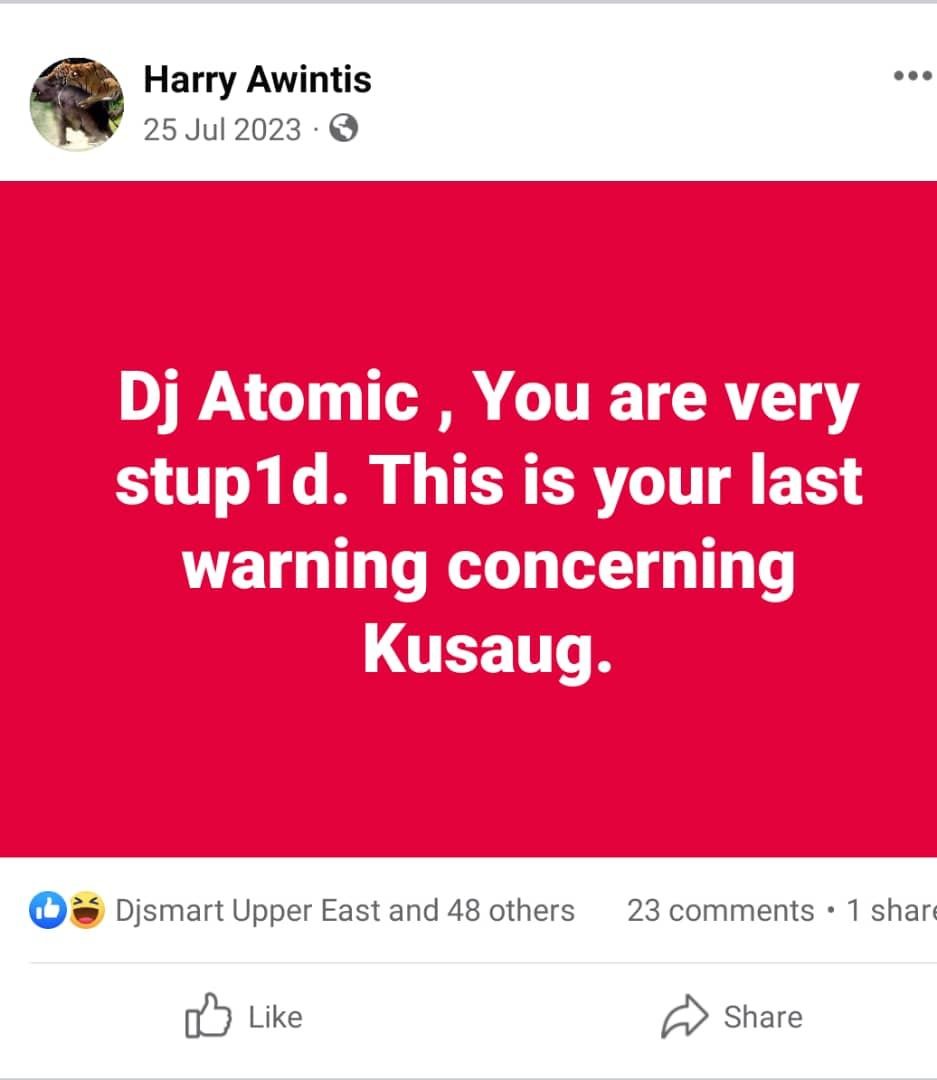

Fig 11: Seidu Mutawakilu and Atungu Iddrisu Kasim(DJ Atomic) of Max Empire threatened on Facebook

Fig 12: Atungu Iddrisu Kasim (DJ Atomic) of Max Empire threatened on Facebook

Another journalist with Source FM who has been threatened online is Simon Asimiga and, in an interview, he revealed the coded language sometimes used in threatening journalists in Bawku.

“They have a way of threatening you and it could be even a proverb. Many a times if you are not from Bawku, you won’t know. If my picture is put on social media by a Mamprusi and the person says 6 feet awaiting, this time you will not survive it, or [that] I can not run more than my shadow. Anyone from Bawku knows that they will kill me if they get me.”

Combat language in Bawku

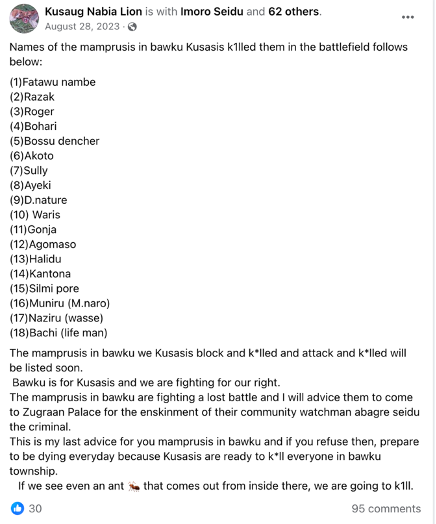

The escalation of the Bawku conflict has come with a shift in combat language used by the actors, leading to the normalisation of terms like “warriors”, “informant”, “spies”, “enemies”, “6 feet” and “battlefield” as the common lexicon in the conflict.

Fig 13: A manifesto posted on Facebook detailing how 18 people were killed on the “battlefield”(here)

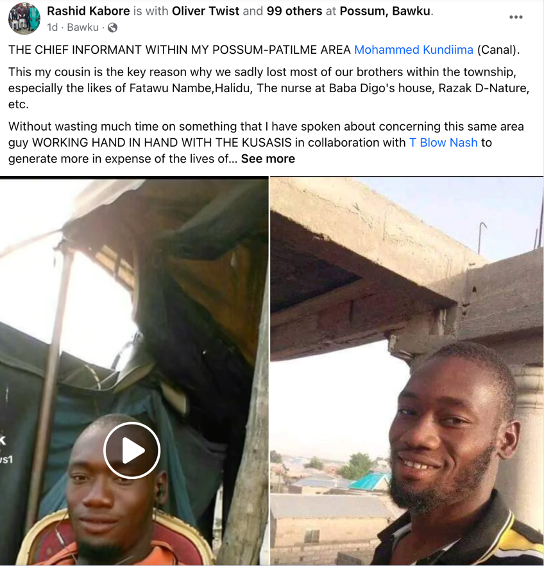

Fig 14: A doxxing attempt on Facebook with the person labelled as a “chief informant”

Fig 14: A doxxing attempt on Facebook with the person labelled as a “chief informant”

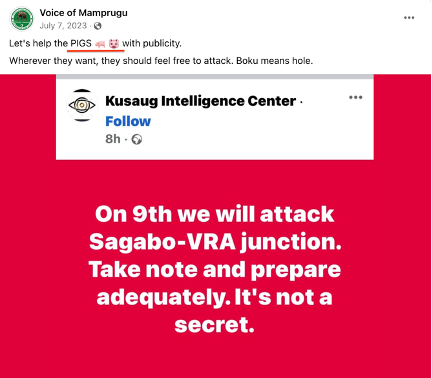

With 5.6 million Facebook users in Ghana, constituting 85% of all social media users, the platform of choice continues to play a significant role in the ongoing Bawku conflict even though many of the tactics and techniques employed by the actors in the conflict are in clear violation of Facebook’s community standards – the guidelines for what is and is not allowed on Facebook.

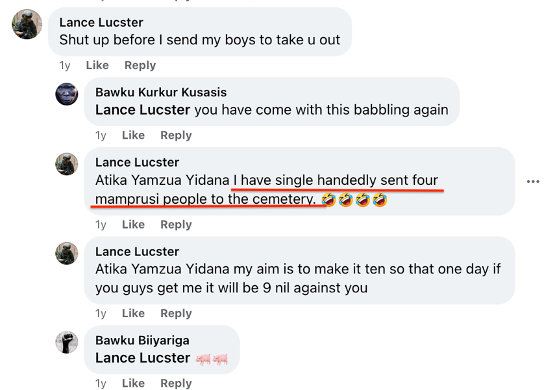

Facebook’s parent Meta warns its users against posting “threats that could lead to death (and other forms of high-severity violence) and admission of past violence targeting people or places” as part of its policy on violence and incitement.

However, that is exactly the playbook employed by the two (2) feuding factions in the ongoing Bawku conflict without any repercussions or enforcement of Facebook’s community standards.

Fig 15: A celebratory Facebook post after the killing of one Razak

Fig 15: A celebratory Facebook post after the killing of one Razak

Fig 16: A Facebook user admitted to killing four (4) people due to the Bawku conflict

The guidelines also bar users from posting hate speech and violent graphic content; with Meta claiming it seeks to promote values like safety, privacy and dignity on its platform.

However, more than two (2) years since the Bawku conflict started, there has been very little to show in the enforcement of Meta’s policies against hate speech and violent graphic content. GhanaFact has collected more than 100 Facebook posts of threats, violent content and hate speech in a database (February 2023 to September 2023) and continues to monitor how maimed victims and graphic content are being weaponized as human trophies on Facebook.

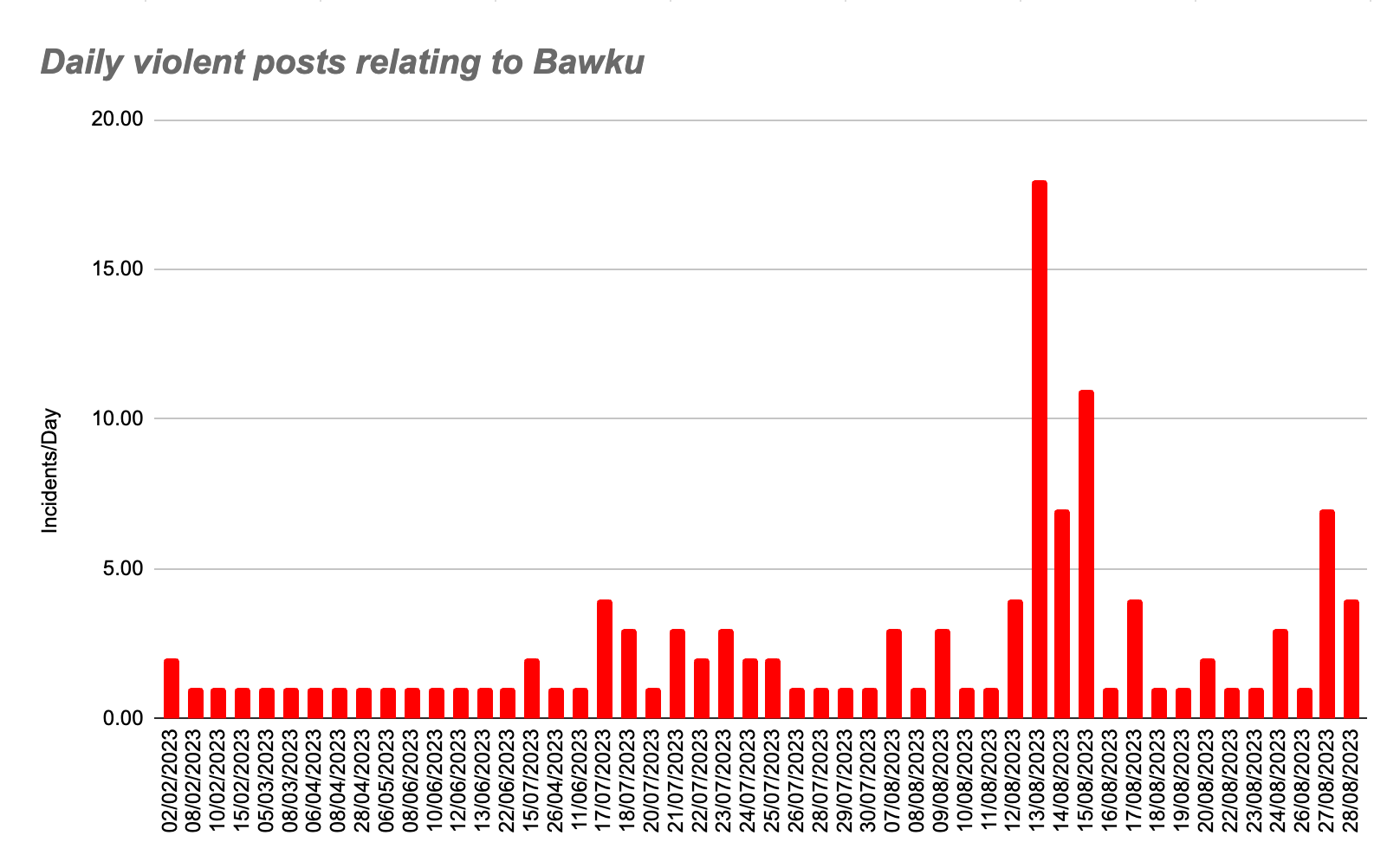

Fig 17: A bar chart depicting how hate speech content relating to the Bawku conflict was shared on Facebook within the 8-month period monitored

The 125 Facebook posts collected and reviewed by GhanaFact showed that there was some correlation between threats issued on social media platforms and eventual attacks and killings that are happening in Bawku. GhanaFact’s monitoring showed that the higher the rate of hate speech shared on Facebook, the higher the likelihood of a physical attack against one of the factions in Bawku.

For instance, August 13, 2023, shows on the chart as the day that recorded the highest number of hate speech content shared on Facebook. Subsequently, on August 14, 2023, GhanaFact’s checks show there was an attack leading to the death of a driver, while 2 others were left injured in Bawku. A closer look at the chart shows there was a gradual build-up in the sharing of hate speech from August 7, 2023, which fuelled the tension in Bawku until the attack.

Again, from August 20, 2023, the chart showed spikes in the sharing of hate speech content on Facebook on some days up until August 27, 2023, when there was an attack leading to the death of 3 people. Another observation from the chart shows that in July 2023, the sharing of hate speech on Facebook manifested into an attack on a bus travelling from Kumasi in the Ashanti region to Bawku in the Upper East region.

Meta touts its range of policies and products, including human moderators, AI algorithms and content rating by third-party fact-checkers, as initiatives that help to detect and flag hate speech, violent/graphic content and mis/disinformation.

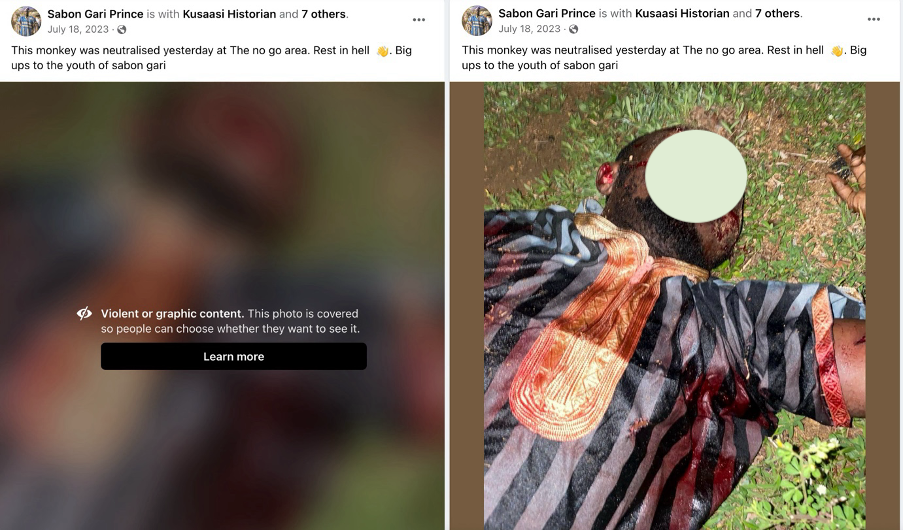

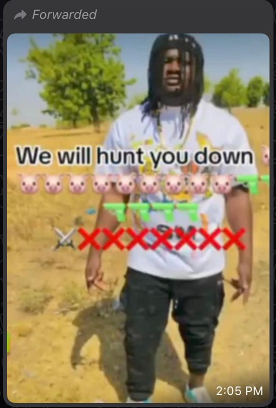

That notwithstanding, in the Bawku situation, GhanaFact has noticed that to avoid triggering the platform’s algorithms, the two feuding sides are using coded language (Kusasis are labelled pigs, and Mamprusis are labelled monkeys), as well as local languages (Kusaal, Mampruli, Moole), and not much has been seen regarding human moderation of hate speech, threats and inciteful posts.

“One may not be able to tell how it started, but what I know is that Mamprusis call Kusasis pigs to liken Kusasis to the senseless and filthy nature of pigs. Kusasis actually call Mamprusis, “Wampris” instead. And a monkey in Kusaal is “Wa’ng”. So the monkey originated from the similarity between the two; “Wampris” and “Wa’ng”,” a local journalist from Bawku who wants to remain anonymous explained.

Fig 18: Pigs are used as a coded word in reference to Kusasis

Fig 19:Monkey is used as a coded word in reference to a Mamprusi

Fig 19:Monkey is used as a coded word in reference to a Mamprusi

WhatsApp and the parading of dead victims as human trophies

In Ghana, WhatsApp is the most widely used messaging app, with 86.3% of all people connected to the internet in the country using the platform. A major selling point of WhatsApp is its end-to-end encryption, where the app assures its users that their messages, photos, videos, voice messages, documents, status updates, and calls are secured from falling into the wrong hands. Thus, the “End-to-end encryption ensures only you and the person you’re communicating with can read or listen to what is sent, and nobody in between, not even WhatsApp,” the popular messaging platform explains in a blog post.

Consequently, this messaging platform serves as a secure medium for sharing information and publicising issues relating to the Bawku conflict. This has made the popular messaging platform a very important resource for actors in the conflict to spread hate speech, incite violence and plan attacks mainly via the voice message functionality. The difficulty in tracing the sources of such information has emboldened the warring factions to engage in the use of this messaging platform to publicise atrocities committed.

While conducting this investigation, GhanaFact sourced several forwarded audio messages on WhatsApp in either Kusaal, Mampruli or Moole languages (spoken by majority and minority ethnic groups in Bawku and surrounding towns) issuing threats to opponents; and calling on people from either side of the faction to take up arms. These threatening audio messages were sometimes cross-published on either Facebook or TikTok; reaching a wider audience to further inflame the conflict.

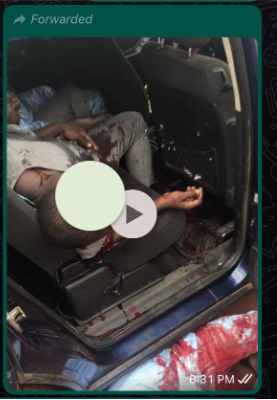

Even worse, WhatsApp has become the preferred channel for sharing violent/graphic content in the form of videos and pictures of dead victims. This is done in the context of showcasing such disturbing graphic content as human trophies – with the two feuding factions seeking to assert their dominance in the conflict. This is also deployed as part of psychological warfare, as it is also used to psyche the support base of each faction in the conflict by creating the impression that the opponent is losing the conflict.

Fig 20: A picture of a now-deceased victim was circulated on WhatsApp

Fig 20: A picture of a now-deceased victim was circulated on WhatsApp

Fig 21: A gruesome video of victims of the Bawku conflict shared on WhatsApp

Fig 22: A graphic picture shared on WhatsApp

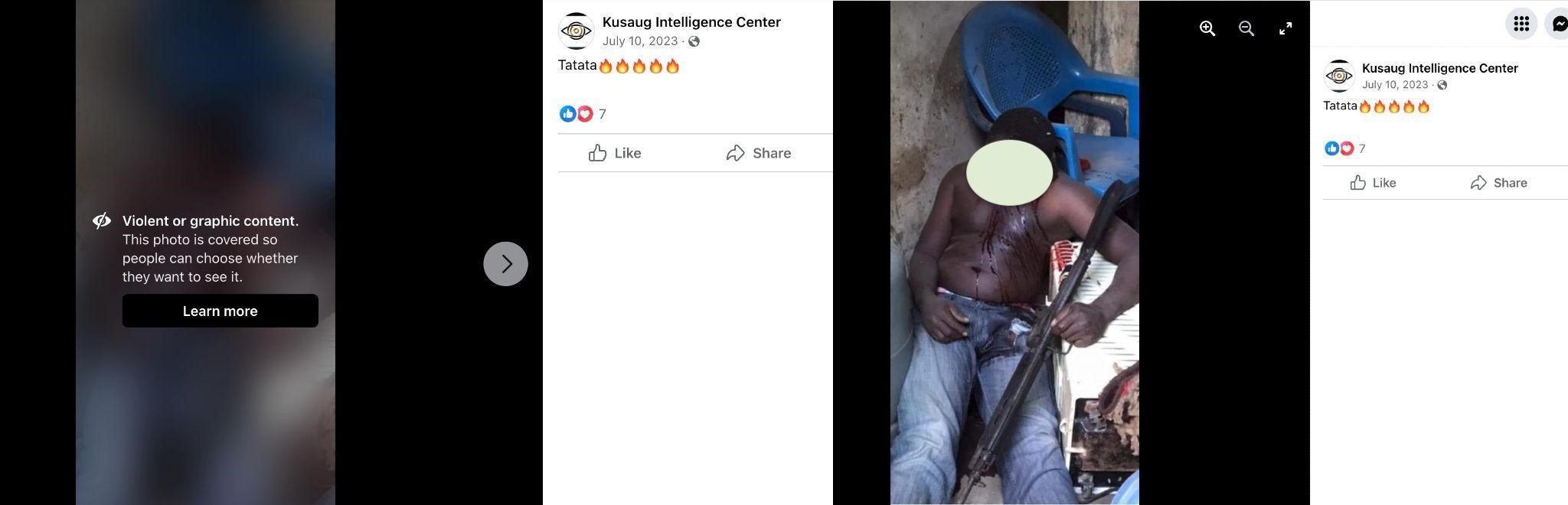

Facebook and TikTok are also channels that are used by some of the actors in the Bawku conflict to display images of maimed persons and pictures of dead victims as human trophies – although Facebook algorithms have proven quite effective in warning users and blurring such graphic images.

Fig 23: A graphic image of a victim in the Bawku conflict posted as a human trophy

Fig 24: Facebook blurs graphic content

Fig 24: Facebook blurs graphic content

Fig 25: A graphic image of a victim in the Bawku conflict posted as a human trophy

According to Meta, it takes a three-part approach to content enforcement: remove, reduce and inform. However, it is obvious from GhanaFact investigations that many Facebook users and pages amplifying the violence in Bawku are doing so without much repercussion despite Meta stating that it will “remove Pages and groups that repeatedly violate the Facebook Community Standards.”

Bawku conflict on TikTok

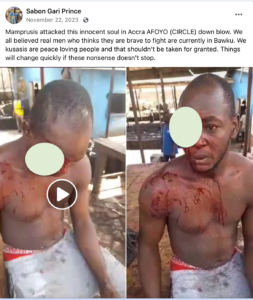

GhanaFact’s social listening over the last couple of months shows TikTok has become another preferred platform for inflaming the conflict by the various actors. The team of investigators continues to collect information relating to hate speech and threats being made by users sympathetic to either of the two feuding ethnic groups in mostly Kusaal, Moole, Hausa and Mampruli (the following hyperlinks are evidence of some of the hate or targeted violent messages that have been used to heighten the conflict (here, here, here, here, and here). Evidently, on November 22, 2023, a group of young Mamprusi men identified and beat up a TikToker who was alleged to have made a video insulting the Nayiri (Enskinned) Bawku Naaba on the social media platform.

Fig 26: A picture of the injured TikToker shared on Facebook

This momentarily sparked violent clashes between the Kusasi-Mamprusi community residents at Circle (Articulator Station and Foryor), a suburb of Accra in the Greater Accra Region. This area is mostly populated by young men and women who have migrated from Bawku to engage in menial work and other forms of business to enhance their well-being and that of their dependents in Bawku.

“They went to Tulaku and organised some guns,” a source told GhanaFact about how a group of Kusasi youth mobilised and stormed the area to avenge the attack on the TikToker.

The resulting clashes and exchange of gunfire saw four (4) people hospitalised with gunshot wounds.

It took the Greater Accra Regional Police Command to restore calm in the area and subsequently engage the youth leaders of the two ethnic groups. However, that did not prevent subsequent attempts to burn down some kiosks (makeshift wooden structures built for accommodation) later that night.

AI weaponised in the Bawku conflict

GhanaFact investigations found that some actors in the Bawku conflict are also weaponising Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) content to polarise the feuding factions further and incite violence.

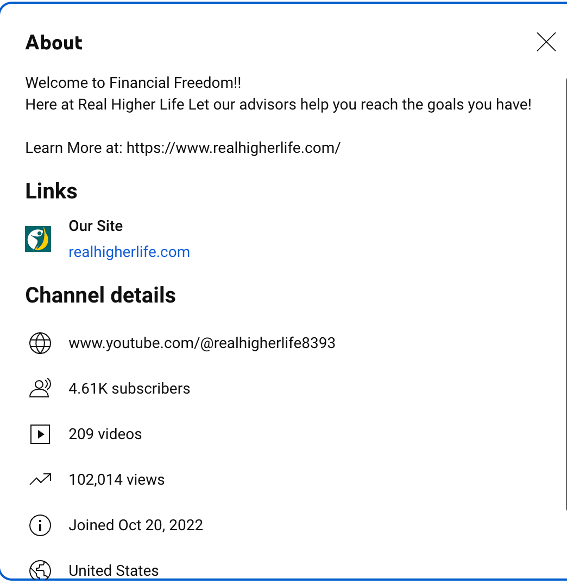

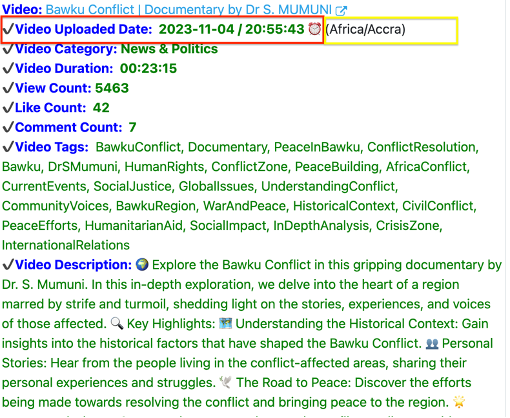

First, our investigators found a 5-minute-36-second-long AI-generated documentary shared on Facebook. A subsequent online search led us to a much longer version of the video documentary, published on a YouTube Channel, Real Higher Life, with more than 4000 subscribers and captioned “Bawku Conflict | Documentary by Dr S. MUMUNI.”

Using YouTube Data Viewer – a tool to extract hidden data from videos hosted on YouTube – the team found that the channel, Real Higher Life, first published the video from a location in Accra on Saturday, November 4, 2023. However, the YouTube channel was originally created in the United States of America just over a year ago, on October 20, 2022, and focuses on AI content creation, AI education, and online finance.

The About section of the channel, which boasts of having advisors that can help viewers reach their financial goals, shows the channel has published 209 videos to date, with the video on the Bawku Conflict being a complete deviation from the platform’s content history.

Fig 27: A screengrab of the profile of the YouTube channel

Fig 27: A screengrab of the profile of the YouTube channel

The name Dr S. Mumuni, which appeared in the title and then in the third frame (00:14) of the video as the creator, cannot be conclusively linked to any known individual. A further content analysis of the video shows that it is an amateur attempt to use AI, piecing together footage from mainstream credible TV platforms, including TV3, Adom TV, Aljazeera, Joy News, Africa News, Metro TV and Citi TV (1,2,3,4), which has garnered 6.8k views over the last two months only on YouTube. To gullible viewers, it can lead to the confirmation bias of some narratives being promoted by the documentary.

The team’s assessment of events shows that less than 40 minutes after Vice President Dr Mahamudu Bawumia was declared winner of the flagbearer contest of the New Patriotic Party (NPP), the AI-generated video was uploaded (at 8:55 pm) onto the video streaming platform.

Fig 28: A screenshot of YouTube Data Viewer assessment of the channel

Fig 28: A screenshot of YouTube Data Viewer assessment of the channel

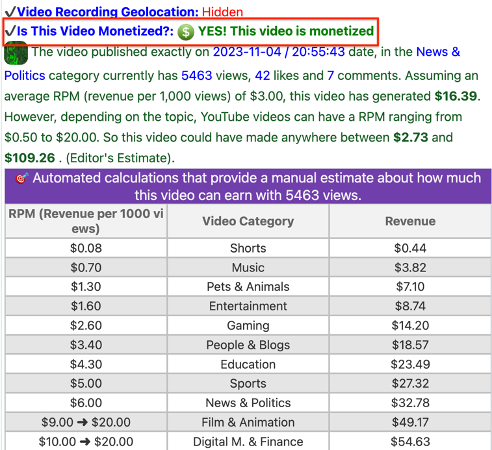

Our investigations show that the AI-generated content has been monetised, and so far, the publisher could have made anywhere between $2.73 and $109.26. Since October 20, 2022, the YouTube Channel “Real Higher Life” has generated more than 100,000 views and assuming all views have been monetised, the channel might have generated about $306.04 over the period.

Fig 29: A screenshot of YouTube Data Viewer assessment of the channel

Fig 29: A screenshot of YouTube Data Viewer assessment of the channel

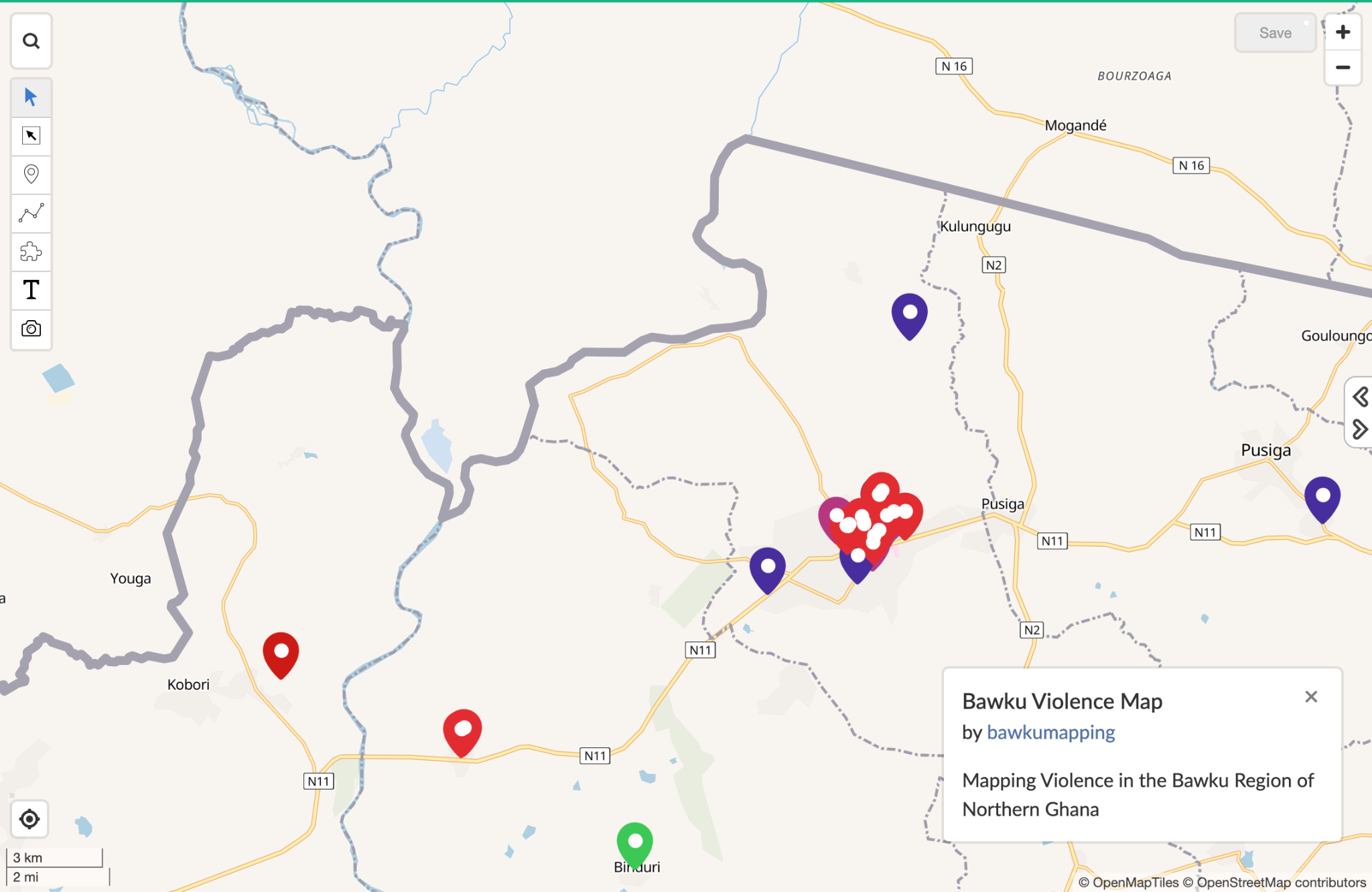

Mapping of the killings

The more than 2-year-old Bawku conflict generally is presented in national discourse as a chieftaincy conflict between the Kusasis and the Mamprusis. However, a closer assessment of “block and kill” attacks that are linked to the conflict shows there have been many casualties outside the main Bawku township.

So far GhanaFact has collected data relating to targeted killings, gun attacks and burning of buses/vehicles in Walewale, Pusiga, Bolgatanga, Binduri, Nasia, Nalerigu, Zuarongo, Accra and Techiman.

Fig 30: A screenshot of a map showing areas in and around Bawku where people have been killed (here)

Fig 30: A screenshot of a map showing areas in and around Bawku where people have been killed (here)

With a population of more than 100,000, Bawku has long been known as a brisk commercial border town, but is now a shadow of itself, due to the conflict. As high as 60.8 percent of households in the municipality are engaged in agriculture and according to a World Bank study, about 90% of the local population in the area are poor.

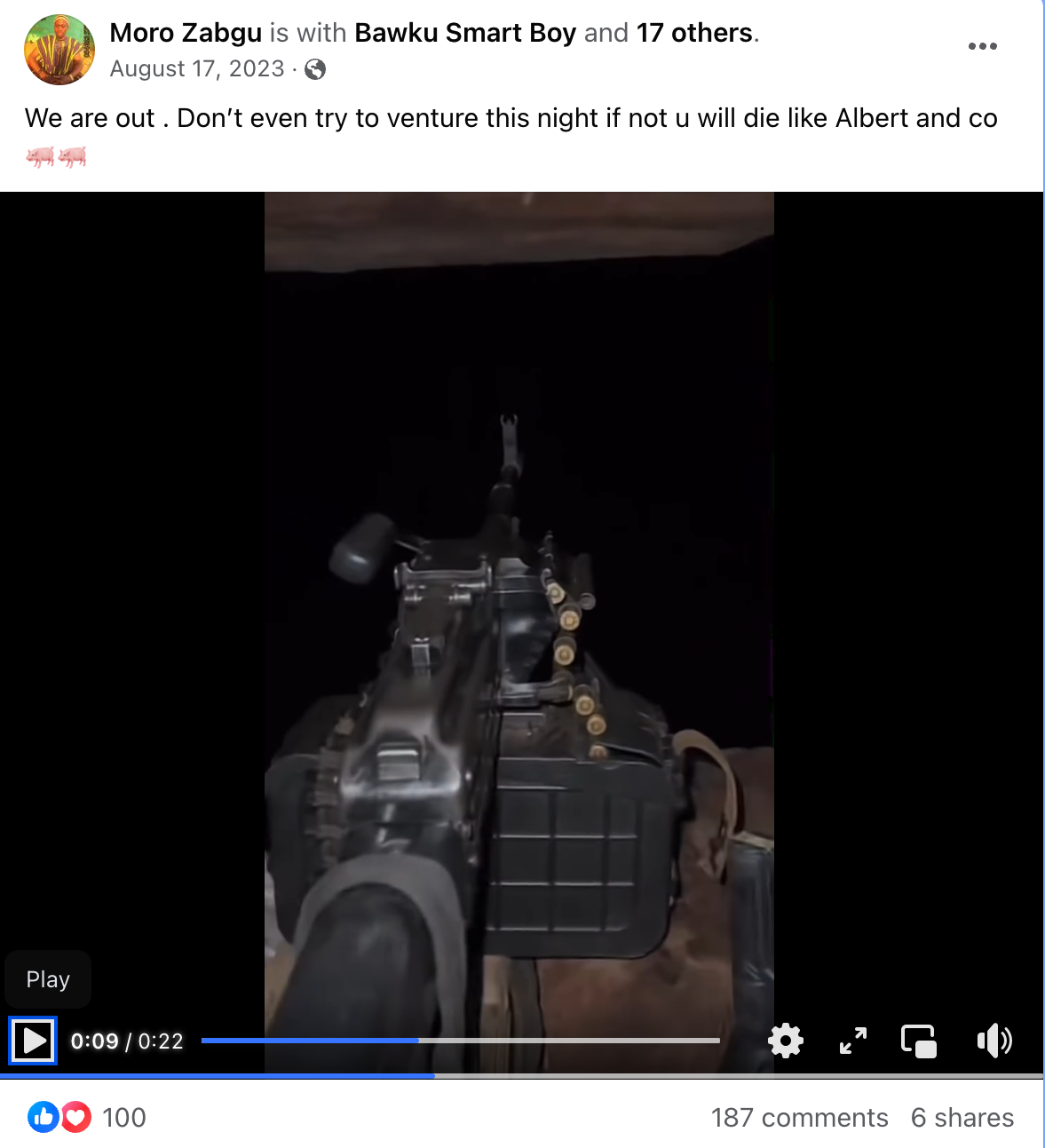

Fig 31: A video of a sophisticated gun allegedly being used by locals in Bawku posted on Facebook (here)

Fig 31: A video of a sophisticated gun allegedly being used by locals in Bawku posted on Facebook (here)

On January 18, 2024, the Ghana Police recovered a Rocket Propelled Grenade (RPG) bomb in Bawku after a failed attempt to destroy a fuel station while there have been many complaints about the stockpile of high-calibre firearms being hoarded by the feuding factions.

The National Communication Authority (NCA) on February 24, 2024, shut down four (4) Radio stations; Bawku FM, Source FM, Zahra FM and Gumah FM.

According to the NCA, the action “follows the recommendations of the Upper East Regional Security Council, and on the advice of the Ministry of National Security that the operations of the said FM Stations and the incendiary utterances of their panelists/presenters have contributed to the escalation of the Bawku conflict, leading to loss of lives and property in Bawku and its environs”.

However, after 7 months the NCA lifted the ban and restored the broadcasting rights to the radio stations after the management signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) to ensure peace in the Bawku municipality.

The Cost of Security

The Ministry of National Security has indicated that the country allocates Gh¢6 million to support the operations of state security, which included the special task force.

“In response to the sharp and troubling escalation of the inter-ethnic tensions in Bawku in 2021, which led to the tragic loss of hundreds of innocent lives, including women and children, displacement of people, and disruption of the economic activities, the Ministry, as a matter of urgency, established a special operation in February 2023 to maintain peace in Bawku and its environs, as well as other areas in the North East Region affected and impacted by the conflict” the statement from the Ministry of National Security said.

According to the Ministry, the funds cover essential operational costs, such as fuel supplies for Armoured Personnel Carriers (APCs) and other operational vehicles; the provision and delivery of food rations for personnel of the Task Force; special intelligence operations, and other civil-military activities.

Conclusion

For over two years, a violent inter-ethnic and chieftaincy conflict has had Bawku in a chokehold. Hundreds have been killed and adverse effects on socio-economic development have impacted daily life in Bawku.

A close to one-year-long open-source digital investigation of some social media pages, groups, and individual accounts shows an obvious weaponization of social media – WhatsApp, Facebook, and TikTok – in perpetuating the conflict.

GhanaFact recommends that the Government of Ghana should investigate the negative use of social media in the Bawku conflict, recognizing that the problem lies in its misuse rather than the platform itself. Also, the Government should collaborate with peace institutions and civil society to collect more credible and verifiable data about casualty counts and the domestic and cross-border socio-economic impact of the conflict.

Regulatory agencies in Ghana, such as the National Communications Authority and the National Media Commission, should enhance their content regulation efforts per existing laws. These commissions should take corrective measures to mitigate the impact of harmful content while acknowledging that the primary issue lies in the negative use of traditional media and social media platforms.

Civil society organizations, the Government, and social media and tech companies should also collaborate to raise awareness about social and ethical standards related to social media usage in the affected community and nationwide.

Finally, social media and tech companies like WhatsApp, Facebook, X, YouTube, and TikTok should enforce

community standards and policies to swiftly address harmful content, including coded and local language posts.

By: GhanaFact